The regional traveler typically wants to pass through town as efficiently as possible and will stick to the highways. The tourists, of course, enter town via these highways, then, like a local, prefer either walking or are OK with moving about the city at a slower pace.

A positive experience for the human is vastly different than that of the car. The car wants wide open lanes without obstructions or having to slow down, and the human wants a cozier city experience like narrow streets, shop fronts and freedom from traffic. The great spaces of cities that bring people together are usually car-less or prioritize the human over the traffic.

I’m not vying for a world without cars, as a daily user of one, but I am proposing a change in how the city prioritizes car reliance over the human experience. The human experience is an afterthought given the priority to highway car traffic. This plan, instead of answering, raises the question of where do we want to invest and how should our city grow?

The Idaho Transportation Department has some preconceived ideas about what makes a good road and “flow” of cars through a city; but, again, this is generally at odds with what makes a good city for a human.

For example: The stretch of U.S. Highway 95 through Coeur d’Alene employs traffic light after traffic light as a “solution” to allow for more flow, but its 200 feet of right-of-way creates physical and mental barriers for the human. Similarly, we have our local barriers like U.S. Highway 2 in Sandpoint, specifically between Sandpoint Super Drug and Big 5. People need to carry bright orange flags to even be seen and avoid getting hit crossing those five lanes of steady traffic.

A successful plan will address these existing intersections and widened highways and, if building new ones, put the human first and car second.

There are economic benefits to individuals, businesses and the city by doing this. In an ongoing, decades-long study in Copehnagen — a city that once had downtowns filled with cars, roadways and parking lots — driving a car cost the government 20 cents per mile, but every time a cyclist rode the same distance, it made 41 cents. These savings are based on the reduced cost of infrastructure maintenance, as well as reduced individual health care costs.

Given there is more public investment in health costs in Copehnagen, in the U.S. this money would instead be going into our own pockets.

Walkability and human-centered spaces have shown to positively impact local businesses and employment opportunities. In one of many studies in New York City, converting underused parking into a public park increased nearby retail sales by 172% (compared to 18% throughout the region).

All this is to say, while the general goals of the plan and a majority of the concept designs seem to be in alignment with what Sandpoint residents desire for a future cityscape, there are key areas that still need to be addressed.

Specifically, a reinvigorated “Curve” design — see the Feb. 1 edition of the Reader, “Remember ‘the Curve’?” and google “2011 Curve, Sandpoint” — which would include two separate one-way highway routes slicing through town, dividing downtown from west Sandpoint. These asphalt canyons would be continuations of Fifth Avenue and Cedar Street traffic.

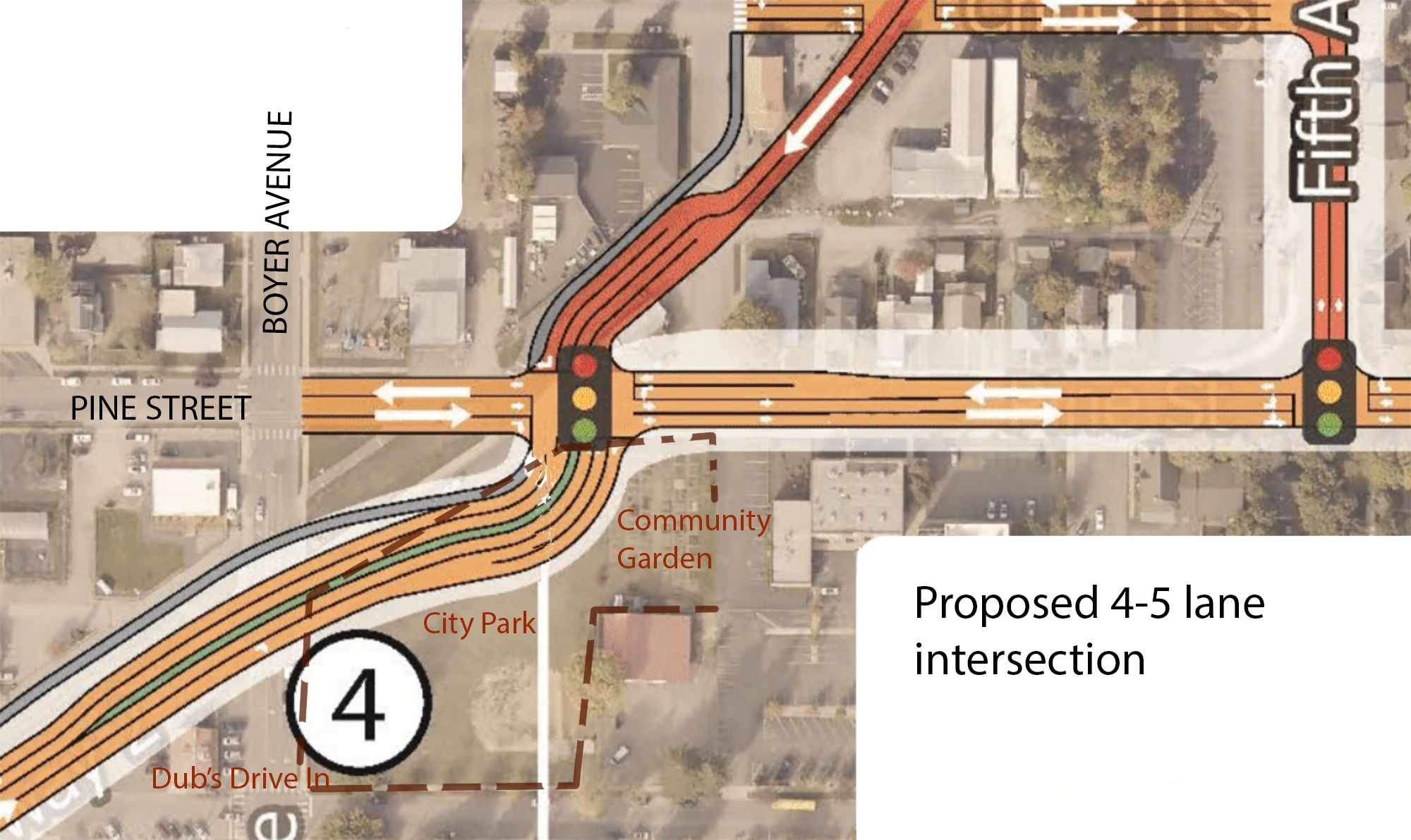

Farther south, it was jarring to see a conceptual new intersection eating into the baseball field. If you look closely enough, you’ll see there are four to five lanes converging on this park.

It seems that our memories of U.S. 95 flowing through downtown — and now diverted by the bypass — have blurred over the years, as we now are looking at repeating an investment in further spreading highway traffic through town, an issue we “fixed” with the $40 million bypass in 2015.

The concepts in this plan are just that, but they are a guide for future investment, of which the highway couplet expansion increase will cost approximately $1 million. Imagine if this money was invested in humans instead of cars, what would a city look like?

I can imagine a few things, such as more thoughtful highway intersections and slowing traffic to better the experience of our city; growing our housing market; creating an inclusive public market, since we’ve lost one recently; and/or a location for a true multimodal transit hub with either busses or tram cars that can easily move people throughout the city.

We invest in what will come true. Build highways for more cars and they will fill that void. As a community, let’s envision and build a city with opportunities for walking, standing and sitting; spaces for people to meet, talk and listen; and for places of play and exercise.

To borrow from Cities for People, by Jan Gehl, “By being sweet to the pedestrian and the cyclist you hit five birds with one stone — you get a lively city, you get an attractive city, you get a safe city, you get a sustainable city and you get a city that’s good for your health.”